A corn mill changes the lives of the people in this frontier village.

The village of Mahayahay is only about 11 kilometers from Poblacion Maragusan, Compostela Valley Province (now Davao de Oro), but because it stands 2,000 feet above sea level, it can take about an hour to get there over rough roads edged with tall cliffs and long drops to the thick forest below. The hardy folk of this frontier town have learned to cope with the sometimes harsh conditions here, growing corn, coffee, and abaca since the 1980s before recently adding sayote, durian, tomato, and bell pepper to the mix.

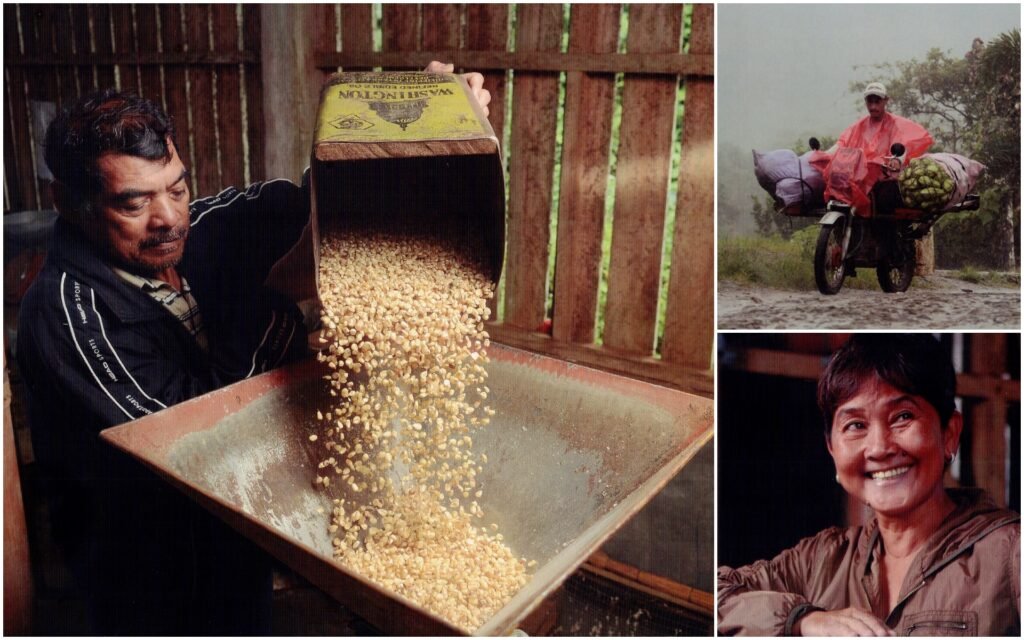

For barangay captain Juanito Torcende, the difficulties of living in Mahayahay are all too real. “We didn’t have a mill here so we had to bring our corn and coffee all the way down to Maragusan for milling and grinding,” he says. That meant carrying a hundred kilos or so on board a rented “Skylab” or locally known as “habal-habal” — a motorcycle fitted with wooden planks vaguely resembling the US space station that crashed in 1979 — and traveling down the treacherous road.

Gemma L Madjos, the chairperson of the Mahayahay Farmers Consumers Cooperative, says taking crops to Maragusan for milling was an expensive undertaking. “The one-way fare for a motorcycle was P100. And of course we had to buy food. To maximize the trip, I would carry as much as 100 kilos of my crops.”

Farmers would often resort to selling their corn and coffee at a lower price so they could buy food for their families. “They would just convert their crops to rice instead of spending for a motorcycle,” Gemma says.

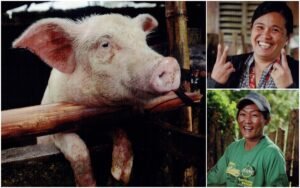

A breath of fresh air came in 2008 when Kasilak came to the barangay to implement the Maragusan Valley Area Resource Development (MaVARD) Project, a three-year partnership with the Catholic Relief Services (CRS) Philippines with funding support from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) under its Food for Progress Program. “They asked us what we needed and the first thing we said was a water system,” Juanito says. After constructing a Banga Pinoy Water Tank, Kasilak continued its support by distributing farm animals, seedlings, and other agricultural inputs to the farmers.

The last thing the barangay requested was a corn mill, which Kasilak provided through the cooperative. “Kasilak also trained us on how to use it and how to set benchmarks,” Gemma says. Soon the cooperative was milling corn not just for farmers of Mahayahay but also of neighboring barangays like Paloc, Parasanon, and Saranga. “We would mill up to 2,000 kilos of corn a day,” Gemma says.

The volume dropped in 2015 when Saranga received its own corn mill from the government, so the cooperative decided to grind coffee as well. “We alternate corn and coffee during the week,” Gemma says. “We charge P3 per kilo for corn and P4 per kilo for coffee. The income goes to the cooperative, and the operator gets a percentage as well.”

Gemma looks back with gratitude at how the corn mill has benefitted the barangay. “We save money because we don’t have to go to Maragusan anymore. More than that, the people are now more willing to produce corn and coffee.”

For Juanito, the biggest benefit of the corn mill is how it has brought the community together. “Kanya-kanya gyud mi sa una (We used to work independently of each other). Now we work hard to produce more because the entire barangay benefits when the corn mill is used by more farmers.”